Overworked & Undervalued: Sustaining the Community Impact Workforce

Part 2 of a 4-part series on sector transformation

Written by ANNIKA VOLTAN, EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR & SANDRA MCKENZIE, CO-FOUNDER OF THE FORGE INSTITUTE

A Healthy Community Impact Sector Starts with a Sustainable Workforce. This article is the second installment in a series focused on generating ideas from you on a healthy Community Impact Sector transformation and recovery!

In our introductory article, “We Need a Healthy Community Sector: Here’s Why You Should Care” we took a big picture view and made the case for why a vibrant community impact sector should matter to all of us. This article examines workforce strengths and challenges as part of the call for fresh ideas and models to ensure the sustainability and vibrancy of this important sector.

Big Economic Impact Sustained by a Precarious Workforce

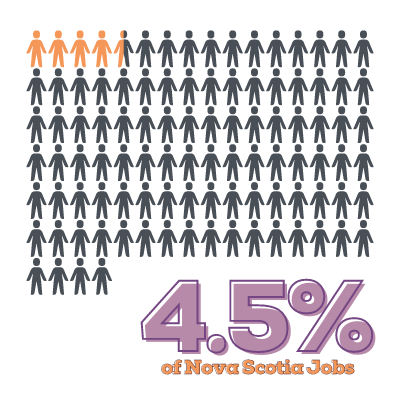

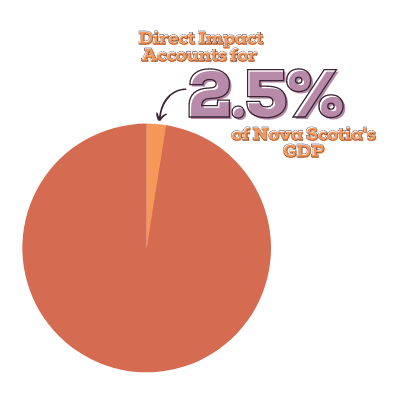

The Atlantic Provinces Economic Council’s (APEC) Report, The State of the Nonprofit Sector in Nova Scotia, completed in 2020 on behalf of the Community Sector Council of NS, paints a picture of the economic impact of the sector, which employs over 20,000 people.

The Atlantic Provinces Economic Council’s (APEC) Report, The State of the Nonprofit Sector in Nova Scotia, completed in 2020 on behalf of the Community Sector Council of NS, paints a picture of the economic impact of the sector, which employs over 20,000 people.

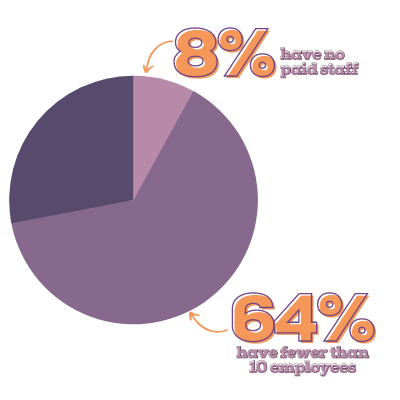

It’s important to keep in mind that most nonprofits are small with 64% having fewer than 10 employees (8% having no paid staff) – and, on average are smaller than in other provinces. Key findings related to the sector’s workforce in NS include:

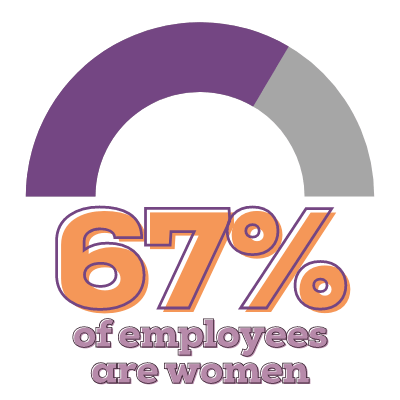

Staff are Predominantly Female and More Diverse than Other Sectors. Women account for 68% of employees, 67% of Executive Directors and 53% of board members. The percentage of total employment in nonprofits is higher than in all industries for the Black population (including African Nova Scotians), recent immigrants (within the last five years) and Acadians, but lower for Indigenous workers.

Staff are Predominantly Female and More Diverse than Other Sectors. Women account for 68% of employees, 67% of Executive Directors and 53% of board members. The percentage of total employment in nonprofits is higher than in all industries for the Black population (including African Nova Scotians), recent immigrants (within the last five years) and Acadians, but lower for Indigenous workers.

The Workforce is Highly Educated and Under-Paid. Nonprofit leaders in Nova Scotia are highly educated, with 84% of leaders having a bachelor’s degree or above as compared to 60% of senior managers in other sectors having a bachelor or master’s degree. However, nonprofit leaders’ wages are lower compared to other senior management positions in the province. Given the higher proportions of women and equity-seeking groups employed in the sector, it’s past time to examine these race and gender wage gaps.

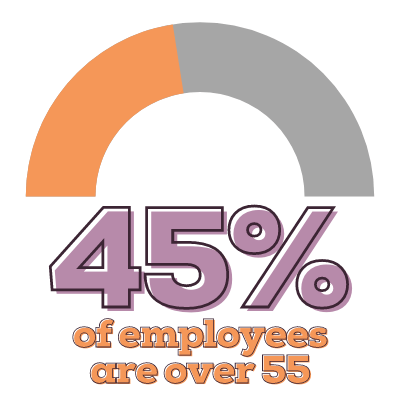

Nonprofit Leaders are Older than Other Managers. 45% are over 55 years old. Despite this, only 35% having a formal succession plan in place. In addition, COVID-19 has catapulted the sector into a digital era where new skillsets are needed for designing and managing virtual communications, events, and programming.

Nonprofit Leaders are Older than Other Managers. 45% are over 55 years old. Despite this, only 35% having a formal succession plan in place. In addition, COVID-19 has catapulted the sector into a digital era where new skillsets are needed for designing and managing virtual communications, events, and programming.

Perceptions of the Sector Lead to Recruitment Challenges. Nova Scotia’s aging workforce is creating labour challenges throughout the economy. Labour and skills shortages will make it more difficult than in the past for nonprofits to find new workers as they will increasingly be competing with other sectors. Recruiting labour was cited as a major or significant obstacle to growth by 41% of nonprofits in the province. Perceptions that the sector is low-paid, benefits are scarce, job security is lacking, and that the work is undervalued contribute to workforce issues. These perceptions are validated and perpetuated by short-term, program-focused funding models – an issue we’ll visit in greater detail in our next article!

Labour Force Challenges are More Complex in a Sector that relies on Volunteers. Nova Scotia has one of the highest rates of volunteerism in Canada with 74 million hours contributed, accounting for 60% of the labour resources required for nonprofit activities. APEC estimates the economic value of volunteer hours in the nonprofit sector in 2018 to be about $1.5. However, volunteer rates have been falling – this decline has been even steeper since COVID-19 as many volunteers are aging and are, themselves, vulnerable to the risks of the pandemic. Attracting new and younger volunteers will be a critical factor behind the success of nonprofits over the next decade and may require new approaches to volunteer recruitment and experiences. Otherwise, nonprofits will have to rely more on paid staff (requiring more funding), automation, or service reduction. To complicate matters further, volunteers are not only needed to run programming, but to sit on boards and help fulfill the fiduciary responsibilities of organizations – another topic we will revisit in more detail later in this series.

Labour Force Challenges are More Complex in a Sector that relies on Volunteers. Nova Scotia has one of the highest rates of volunteerism in Canada with 74 million hours contributed, accounting for 60% of the labour resources required for nonprofit activities. APEC estimates the economic value of volunteer hours in the nonprofit sector in 2018 to be about $1.5. However, volunteer rates have been falling – this decline has been even steeper since COVID-19 as many volunteers are aging and are, themselves, vulnerable to the risks of the pandemic. Attracting new and younger volunteers will be a critical factor behind the success of nonprofits over the next decade and may require new approaches to volunteer recruitment and experiences. Otherwise, nonprofits will have to rely more on paid staff (requiring more funding), automation, or service reduction. To complicate matters further, volunteers are not only needed to run programming, but to sit on boards and help fulfill the fiduciary responsibilities of organizations – another topic we will revisit in more detail later in this series.

Given these issues, workforce recruitment, retention, succession planning, and compensation need to be central to a Sector Transformation and Recovery Strategy. They are part of the ball of “silly string” that needs to be unraveled and considered in the context of other challenges facing the sector.

Undervaluing the Sector Exacerbates Workforce Challenges

There are a number of contributing factors to the challenges being experienced by the sector. In an Open Letter to the Canadian Government[1], Margaret Mason, the Chair of the Board of Imagine Canada, a pan-Canadian organization states, “Dedicated to bolstering the charities, nonprofits and social entrepreneurs that build, enrich and define our nation and the communities they support“, which lays out a compelling business case to value and invest in the nonprofit sector:

The Sector is Not Measured or Tracked

The Sector is Not Measured or Tracked

The nonprofit sector contributes 8.5% to the Canadian GDP – more than the construction, energy, transportation, or agriculture sectors – and employs 2.4 million people or 12% of Canada’s labour force.[2] Despite this, the sector seems to be largely invisible to the government. Every year, Statistics Canada collects detailed information on male-dominated industries that employ fewer people and account for less GDP than the nonprofit sector, yet has not conducted a single survey of the nonprofit sector since 2003.

Gender Bias

Gendered perceptions of the nonprofit sector have an enormous impact on sector workers. Common funding practices, such as short-term contracts and extensive monitoring and reporting requirements, reflect a view that nonprofit workers are unskilled, untrustworthy and need to be carefully monitored. These funding practices, combined with general societal attitudes about nonprofit work, mean that workers often face low wages with few or no benefits and that many jobs are part-time and/or short-term.[3] It is also important to note that much of the labour performed in the nonprofit sector is unpaid.[4] Volunteers are one of the sector’s greatest strengths, but their presence also contributes to perceptions that negatively impact sector workers (e.g., that workers should volunteer their time or at least not expect to be paid the same as those working in other sectors).

Multitasking to the Extreme

Nonprofit leaders and staff showed up in a big way in COVID-19 response efforts and became the face of community outreach and hope during the darkest days of the pandemic. Researchers found that “Mission, passion, will and determination were integral to sustaining non-profits over this time including long hours, maintaining a flexible outlook and mental tenacity“.[5] Unfortunately, working with limited resources is all too familiar to those in the sector, but the additional strains during this time have put many over the edge. A CSCNS survey conducted in the spring of 2021[6] revealed that managing workload and burnout, and addressing mental health in the workplace, are the top two aspects of workplace culture that organizations want to be better equipped to address.

In addition to complex, stressful work environments, nonprofit leaders and staff set high standards for themselves and face high expectations from their boards and funders. Many Executive Directors and founders are drawn to the sector based on personal experiences and passion and, as a result, learn on the job. But this is not an easy role to navigate – given the small staff sizes, leaders are expected to not only possess the hard skills that make an organization function (financial management, fundraising, human resource management, program knowledge, governance, planning and community relations and communication skills[7]), but are also expected to have the soft skills which bring heart to the work they do (compassion, empathy, inspiration, community-building, multi-faceted relationships). In addition, they are tasked with the strategic work of partnership building, collaboration, reaching consensus, and pursuing new opportunities.

High expectations indeed for a group that is highly educated and underpaid. It’s no wonder that coping with burnout, overwhelm and mental health in the workplace are emerging as top concerns. But it’s not all doom and gloom – if we can find ways to make the workload more sustainable and supported, there are many young workers who are drawn to the potential of the impact they can have in this sector.

Addressing The Sector’s Workforce Challenges Will Take Teamwork

What if we acknowledged the Community Impact Sector’s contribution to our quality of life in Nova Scotia by respecting, investing in and fairly compensating the people that do the work?

The Community Impact Sector is not a homogeneous group. Many of the organizations carry out front line delivery of programs and services for government including health, education, child protection, newcomer settlement, and more. Other organizations focus on sports and recreation, arts, housing and the environment. The diversification of scope is both a strength and a weakness, as it’s hard to measure the multiplicity of efforts. But their collective impact is what holds communities together across our province and raises our quality of life. They are the groups that know who needs help, what their local area could benefit from, and how to navigate local systems.

Despite their importance in community cohesion and service delivery, when it comes the sector’s workforce challenges, organizations largely face them on their own. A quick internet search reveals the Community Impact Sector is being advised to:

- Attract the people and talent required for a rapidly changing field, to address new and growing demands for community services.

- Build the skill sets of existing employees, to prepare for changing demands.

- Adapt to an aging workforce.

- Reflect and engage the cultural diversity of communities.

- Respond innovatively to increased income generation and accountability requirements.

- Ensure robust and strategic support for communities to develop innovative solutions that respond to economic, health, and social concerns.

Great advice! The challenge is that the current piecemeal funding model does not include core investment in workforce renewal and skill development, and these are not strategies that can be financed one bake sale at a time.

Key to addressing the workforce challenges in the Community Impact Sector will be sustained partnerships focused on fresh ideas and new models. Because the relationships are symbiotic, the solutions need to be collaborative. A joint effort by all the pillars of society: government, community, businesses and philanthropists, will be required to make sure the house we have built not only stands but can continue to throw open its doors for all.

The 2020 APEC report found that, “While many may appreciate the social contribution of nonprofits, few people truly understand their economic impact or the challenges that are keeping the organizations in this sector from fulfilling their potential.”

The time for that to change is now.

We want to hear from you!

Please consider taking a few minutes to share your ideas for sector transformation and recovery!

Share Your Ideas Here!

[1] March, 29, 2021, Imagine Canada, Chair of the Board, Margaret Mason, OPEN LETTER ON ADVANCING GENDER EQUALITY BY INVESTING IN THE NONPROFIT SECTOR, https://www.imaginecanada.ca/en/360/open-letter-advancing-gender-equality-investing-nonprofit-sector

[2] 1 https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/daily-quotidien/190305/dq190305a-eng.htm;

https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3610040101;

https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/t1/tbl1/en/tv.action?pid=3610061701

[3] Senate of Canada, Report of the Special Senate Committee on the Charitable Sector, 2019, p. 33-36; Ontario Nonprofit Network, Women’s Voices: Stories about working in Ontario’s nonprofit sector, 2018, p. 20.

[4] 3 Statistics Canada estimates that volunteers contributed 1.7 billion hours of labour in 2018, which is the equivalent to 863,000 full-time year-round jobs. https://www150.statcan.gc.ca/n1/pub/45-28-0001/2020001/article/00037-eng.htm

[5] January 31, 2021. How COVID-19 could transform non-profit organizations. Brent McKnight

Associate Professor, DeGroote School of Business, McMaster University and Julie Gouweloos

Instructor, McMaster University. https://theconversation.com/how-covid-19-could-transform-non-profit-organizations-153254

[6] September 2021. “Understanding Capacity Needs in Nova Scotia’s Community Impact Sector”. https://ions.ca/wp-content/uploads/2021/09/Capacity-Building-Survey-Report-FINAL.pdf

[7] The Third Sector, 2020. NonProfit Leadership Development: The Importance of Leadership in Nonprofit Organizations https://thirdsectorcompany.com/importance-leadership-nonprofit-organizations/

[8] The Moran Company, 2020. 5 Soft Skills For Nonprofit Executive Directors Without Prior Fundraising Experience. Paul Gemeinhardt, M.S.W https://morancompany.com/5-soft-skills-for-nonprofit-executive-directors-without-prior-fundraising-experience/

0 Comments

Trackbacks/Pingbacks